Interview by Claire Capel-Stanley

Claire Capel-Stanley: Let’s start with your subject matter because I think it’s really interesting that the series is so specific - young women, living in share houses, photographed in their own homes. Why this subject?

Madeline Bishop: This project was my masters work at the VCA, which I had moved to Melbourne to undertake. At the beginning of the course, I had an overwhelming sense of imposter syndrome, I was a lot younger and less established than my peers, and I felt like I must have slipped into the course by mistake. I think this feeling had a lot of influence over the tangibility and personal nature of the subject matter I chose. I wanted to work from an experience that I lived and felt that I could speak for.

CC: I can definitely understand that feeling! That sense of hesitancy and being ‘not quite ready’, maybe, is throughout the series. It actually becomes a strength, though not something we are used seeing reflected that way.

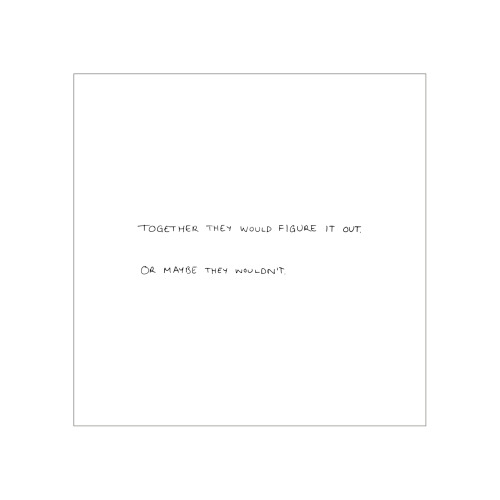

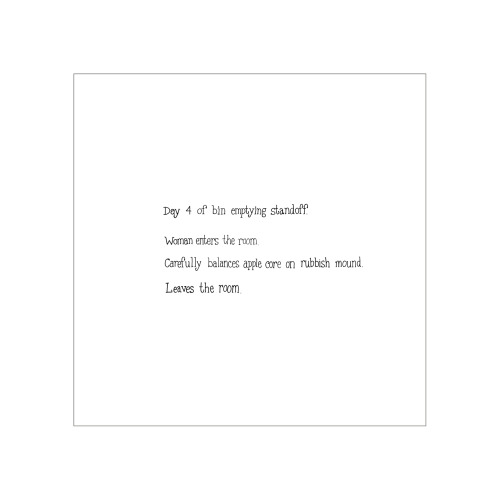

MB: Yes this feeling of inadequacy is part of what formed the titled The In Between. So many women I spoke to had finished the study and were either unemployed or still working in jobs they considered temporary. This appears to be the case for many young Australians, as the youth unemployment rate is double the national average, and university graduates are finding it harder to secure professional jobs in their field. In many ways, the women considered themselves in-between the important or defining stages of their life, much like the social attitude towards the share house space itself. Many of the subjects expressed that they thought they would be in a different place to where they are now and that this in-between stage had become extended, without a clear end in sight. It begs the question; can we continue to consider it a space in-between what we should be doing if it becomes almost permanently where we exist? A problem I continually gauged from conversations with my subjects, and from my own experience, is how we define ourselves when we are perpetually in a liminal stage.

CC: To what extent are these images reflective of your own life?

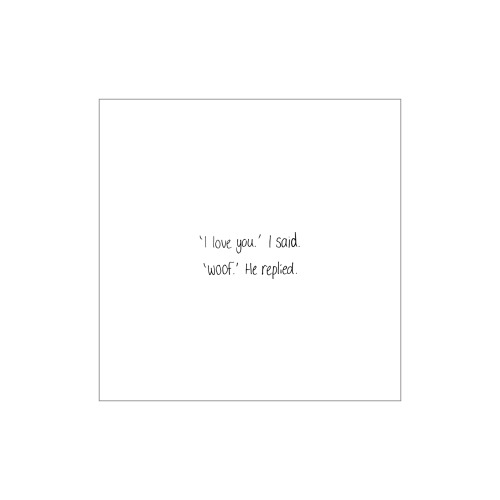

MB: The project is very driven by personal experience and anecdotes or stories told from women around me. It felt like we were all going through a formative period that had been overlooked as important in the grand story of our lives. Intimacy and formative relationships are often thought of in romantic terms, which as we all know is a highly explored concept in art, literature and popular culture. I felt that female relationships were denied importance in mainstream representations, which didn’t reflect my experience that we can be as radically shaped and influenced by our female friendships than our romantic relationships.

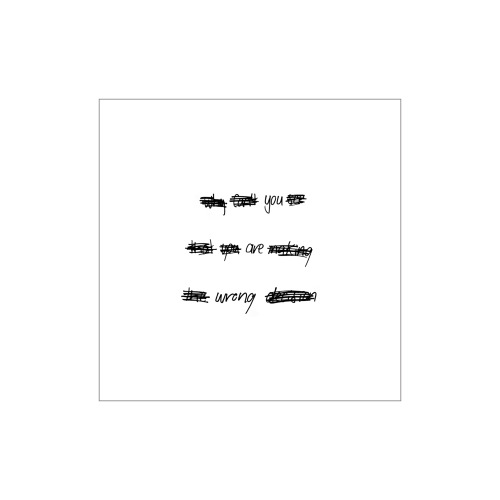

CC: A lot of people seem to have an issue not with the subject matter, but the way the series refuses narrative cohesion. Sometimes, people just can’t get what is meant to be ‘happening’. Have you been surprised by that reaction?

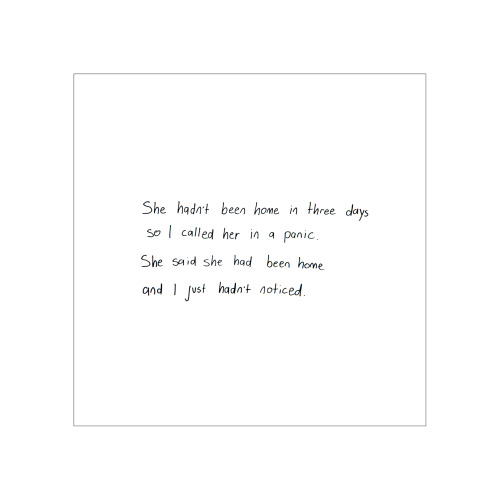

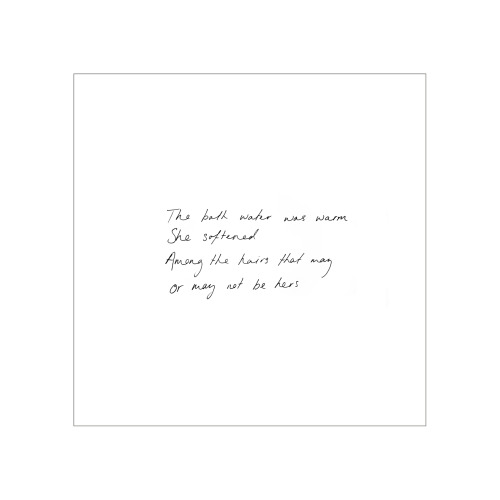

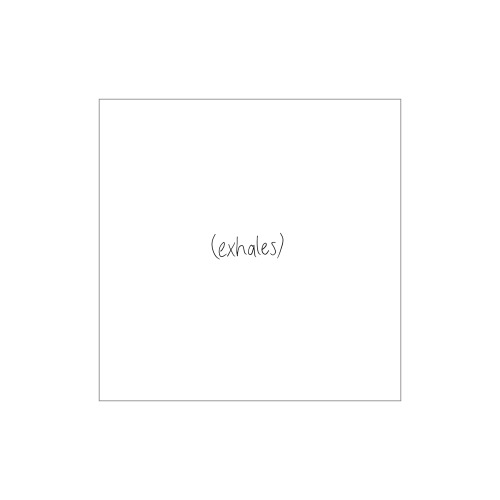

MB: No, I certainly was not surprised. So much of our expectations of what we should get from looking at photography derives from screen culture. This environment has long preferenced male-driven stories that emphasise narrative, action, violence, plot twists. I wanted to flip this and try to reveal the intricacies of down moments, lulls in the action, to see what emotion or tension might exist in these spaces. The images are constructed to be very formal and reminiscent of paintings and scenes of importance. This was intended to add to this expectation that something must happen, that it must be worthy of the monumental scale and scene. I wanted the work to deny the delivery of the ‘aha’ moment that the audience has been accustomed to receiving.

CC: The idea of photographing without an event or action is fascinating - in a way, it seems to go against the whole identity of photography. What did you gain from going against the idea of an ‘event’?

MB: I want my photographs to be questions and not answers. I think in rejecting a clear answer you can invite the audience to think about why we demand images to satisfy us, particularly when it comes to images of women. I want the viewer to question why they are looking at this image of a woman and what they have been conditioned to expect from it. Throughout history, images of women have been made for consumption. I wanted to subvert the act of voyeurism that pervades looking at images of people and historically, culturally, looking at women.

CC: This idea reminds me of the fact that we’re witnessing a profound social change with the #metoo movement. Rather than only legal solutions - which are also important - I think the issue involves questioning the whole armature of sex and power, of which visual culture is a significant part. How do we keep that space of questioning open?

MB: We need to think about what is at the core of a culture ready to enable or turn a blind eye to gender-based violence. I think that core is inherently related to the perception of ‘woman as an object’. If such a large portion of visual representations position women as objects of male desire, then it should come as no surprise that some men believe women exist in the real world to fulfil their desires. Obviously, this needs to change, and I think that arming more women and other marginalised groups with storytelling tools and platforms will help to change this perspective that has dominated visual culture historically.

CC: You’ve drawn on art history quite deliberately in this series - why was it important to ‘speak back’ to the history of depictions of women?

MB: This series was largely about the expectations placed on women and the way that their roles have been shaped by depictions in cinema, art and media. I wanted to call these representations to mind when looking at the work and reflect back a different image of women. In saying this, I wasn’t trying to reflect back some sort of new ideal of the perfect woman, I wanted to reflect back something that could speak honestly to the real, complex and flawed characteristics of actual women and their relationships with one another.

Please consider following PHOTODUST on Twitter and Instagram.